Difference between revisions of "What is a Cyborg?"

Caseorganic (Talk | contribs) |

Caseorganic (Talk | contribs) |

||

| (13 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

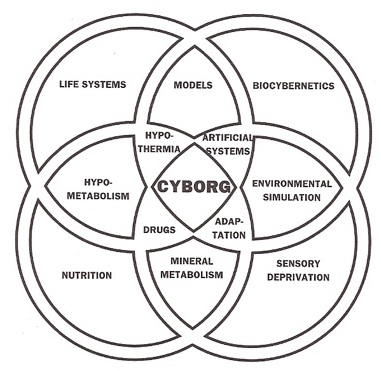

| − | + | [[File:cyborg-venn-diagram-what-is-a-cyborg.jpg|400px|thumb|right|Cyborg Venn Diagram]] | |

| + | ===Definition=== | ||

| + | Anything that is an external prosthetic device creates one into a cyborg. The idea of a cell phone being a technosocial object that enables an actor (user) to communicate with other actors (users) on a network (information exchange and connectivity) makes one into what David Hess calls low-tech cyborgs: | ||

| − | "I think about how almost everyone in urban societies could be seen as a low-tech cyborg, because they spend large parts of the day connected to machines such as cars, telephones, computers, and, of course, televisions. I ask the cyborg anthropologist if a system of a person watching a TV might constitute a cyborg. (When I watch TV, I feel like a homeostatic system functioning unconsciously.) I also think sometimes there is a fusion of identities between myself and the black box" ( | + | "I think about how almost everyone in urban societies could be seen as a low-tech cyborg, because they spend large parts of the day connected to machines such as cars, telephones, computers, and, of course, televisions. I ask the cyborg anthropologist if a system of a person watching a TV might constitute a cyborg. (When I watch TV, I feel like a homeostatic system functioning unconsciously.) I also think sometimes there is a fusion of identities between myself and the black box" ([[The Cyborg Handbook|Gray]], 373). |

| − | === | + | ===Types of Cyborgs=== |

| − | "According to the editors of The Cyborg Handbook, cyborg technologies take four different forms: restorative, normalizing, reconfiguring, and enhancing (Gray | + | "According to the editors of The Cyborg Handbook, cyborg technologies take four different forms: restorative, normalizing, reconfiguring, and enhancing ([[The Cyborg Handbook|Gray]], 3). Cyborg translators are currently thought of almost exclusively as enhancing: improving existing translation processes by speeding them up, making them more reliable and cost-effective. And there is no reason why cyborg translation should be anything more than enhancing". Source: [http://home.olemiss.edu/~djr/pages/writer/articles/html/cyborg.html Cyborg Translation] |

| + | |||

| + | === Consumptive vs. Necessitative Prosthetics === | ||

| + | I'd additionally define two additional types of cyborgs based on consumptive practices: those who attach prosthetics as a necessity, and those who attach them as an external representation of status and tribal affiliation. In the latter case, one's external prosthesis is chosen carefully and updated frequently. This is most often seen in middle classes, especially in the young offspring of these classes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <private> | ||

| + | '''Under Construction''' | ||

| + | In all societies, consumptive practices are tied to identity. | ||

| + | Differentiate between two types of prosthetics: | ||

| + | Necessary (in modern society) | ||

| + | and Aesthetic | ||

| + | And the hybrid line between the two. One that is functional and aesthetic, but comes in different value levels. (Purchasing groups and demographics). | ||

| + | |||

| + | In Simians, Cyborgs, and Women, Harway explained that the cyborg is "a hybrid of machine and organism, a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction. Social reality is lived social relations, our most important political construction, a world-changing fiction" (149). And in her 1997 book she repeats that definition and proposes a cyborg anthrology to study border relations between the two: "The cyborg is a cybernetic organism, a fusion of the organic and the technical forged in particular, historical, cultural practices. Cyborgs are not about the Machine and the Human, as if such Things and Subjects universally existed" (51). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Haraway proposes what she terms a "cyborg anthropology" to study the relation between the machine and the human, and she adds that it should proceed by "provocatively" reconceiving "the border relations among specific humans, other organisms, and machines" (52). One result of unexpected result of such a provocative approach is the recognition that attempts to establish binary oppositions between human and machine, people and technology, has disturbing parallels with racism: | ||

| + | |||

| + | The history and current politics of racial and immigration discourses in Europe and the United States ought to set off acute anxiety in the presence of these supposedly high ethical and ontological themes. I cannot help but hear in the biotechnology debates the unintended tones of fear of the alien and suspicion of the mixed. In the appeal to intrinsic natures, I hear a mystification of kind and purity akin to the doctrines of white racial hegemony and U.S. national integrity and purpose that so permeate North American culture and history. I know that this appeal to sustain other organisms' inviolable, intrinsic natures is intended to affirm their difference from humanity and their claim on lives lived on their terms and not "man's." The appeal aims to limit turning all the world into a resource for human appropriation. But it is a problematic argument resting on unconvincing biology. History is erased, for other organisms as well as for humans, in the doctrine of types and intrinsic purposes, and a kind of timeless stasis in nature is piously narrated. The ancient, cobbled-together, mixed-up history of living beings, whose long tradition of genetic exchange will be the envy of industry for a long time to come, gets short shrift. (60) | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the cyberpunk science fiction , anime , and cinema considered in English 111 , what examples have you found of what Haraway terms "the western theme of purity of type, natural purposes, and transgression of sacred boundaries"? | ||

| + | |||

| + | Follow for a classification of cyborg entities. | ||

| + | |||

| + | =====References===== | ||

| + | *Donna J. Haraway. Modest_Witness@Second_Millennium. FemaleMan©_Meets_OncoMouseª: Feminism and Technoscience. New York and London: Routledge, 1997. | ||

| + | *Donna J. Haraway. Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. Routledge, 1991 [http://www.cyberartsweb.org/cpace/cyborg/anthro.html] | ||

| + | *Harway on Cyborg Anthropology, Human-Machine Relations, and Racism | ||

| + | *Cyborgs among Us: Bodies and Hypertext | ||

| + | *Diane Greco, Program in the History and Social Study of Science and Technology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Cyborgs among Us: Bodies and Hypertext=== | ||

| + | ''This essay appeared originally in Hypertext '96: The Seventh ACM Conference on Hypertext, N.Y.: ACM, 1996, 87-88.'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Certainly the traditional boundaries between humans and machines have undergone a near-dissolution in recent years. Most of us already know people with pacemakers, reconstructed joints, or artificial or transplanted organs. By means of their bodily incorporation of machine (and especially computer) technology, these people dissolve the distinction between organisms and machines. Their status as " cyborgs" -- part human, part machine -- exposes the leakiness of the distinction between technology and nature. By questioning the traditional method of defining what is human (which usually entails comparisons with creature that fall into an equally badly-defined category of what is not), they question our received notions of what it means to be human. Through them, we begin to recognize the limited utility of the distinction between nature and culture. As Donna Haraway puts it, " Our machines are disturbingly lively, and we ourselves frighteningly inert" [152]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Thinking about cyborgs provides a way to talk about bodies without losing sight of the material (or technological) conditions that ground their lived experience. As we learn that bodies are susceptible to technological augmentation and enhancement, we find that the so-called natural body isn't quite so natural, unconstructed, or innocent after all. But talking about cyborgs means talking as much about technology as about bodies, and talking even more about how received conceptions of both bodies and technology uphold the very structures and processes that gave rise to such distinctions in the first place. As technological reconstructions of the body become commonplace, it is necessary to confront technology's political dimension, as a power to shape individuals -- to shape the body politic. Just as cyborgs integrate a variety of technological prostheses in order to constitute their own subjectivities, hypertext writing allows both reader and writer to weave their own meanings from a set of disparate textual elements. Hypertext, as a literal embodiment not only of postmodern fragmentation but also its possible resolution, repeats the cyborg paradigm on a textual, narrative level. Of course, a hypertext resists closure; as others have argued, a hypertexts resists endings, final validations or refutations of the reader's point of view. [See Harpold and Joyce] But perhaps we should not take our satisfactions for granted: perhaps the need for, and satisfaction of, closure is merely a special case of the desire to objectify and classify in the first place, a denial of subjectivity to others with equal, if occluded, claims to it. In that case, hypertext shares not only the cyborg insistence on patchwork subjectivity, a narrative " art of making do," but also the cyborg resistance to final determination or characterization, a resistance with consequences that are not only intellectual and theoretical, but also political -- as a technology with consequences for material bodies as they ground actual lives. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Hypertext thus exemplifies the permeability of the boundary between organisms and machines, as it is embodied in the cyborg paradigm. But without an exploration of its implications, this observation of the uncanny resemblances between hypertext and cyborgs is merely academic; that is, in order for a hypertextually-motivated collapse of categories such as nature and culture to have real consequences, a politics of hypertext must be articulated. Early hypertext pioneers had some inkling of the political ramifications of such a close coupling of bodies and machines. Yet, despite hypertext theory's embrace of avant garde literary productions and its sympathies with postmodern literary criticism, it has yet to come to grips with the political questions hypertext poses for the relation of people to machines. | ||

| + | |||

| + | http://www.cyberartsweb.org/cpace/ht/greco4.html | ||

| + | </private> | ||

==== Other specialized cyborg types: ==== | ==== Other specialized cyborg types: ==== | ||

| − | * | + | *[[Glossary:Protocyborg|Protocyborg]] |

| − | * | + | *[[Glossary:Neocyborg|Neocyborg]] |

| − | * | + | *[[Glossary:Hypercyborg|Hypercyborg]] |

| − | * | + | *[[Glossary:Retrocyborg|Retrocyborg]] |

| − | * | + | *[[Glossary:Pseudoretrocyborg|Pseudoretrocyborg]] |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | 1. Cyborgs actually do exist; about 10% of the current U.S. population are estimated to be cyborgs in the technical sense, including people with electronic pacemakers, artificial joints, drug implant systems, implanted corneal lenses, and artificial skin. A much higher percentage participates in occupations that make them into metaphoric cyborgs, including the computer keyboarder joined in a cybernetic circuit with the screen, the neurosurgeon guided by fiber optic microscopy during an operation, and the teen gameplayer in the local videogame arcarde. "Terminal identity" Scott Bukatman has named this condition, calling it an "unmistakably doubled articulation" that signals the end of traditional concepts of identity even as it points toward the cybernetic loop that generates a new kind of subjectivity ([[The Cyborg Handbook|Gray]], 322). | |

| − | + | 2. This merging of the evolved and the developed, this integration of the constructor and the constructed, these systems of dying flesh and undead circuits, and of living and artificial cells. have been called many things: bionic systems, vital machines, cyborgs. They are a central figure of the late Twentieth Century. . . . But the story of cyborgs is not just a tale told around the glow of the televised fire. There are many actual cyborgs among us in society. Anyone with an artificial organ, limb or supplement (like a pacemaker), anyone reprogrammed to resist disease (immunized) or drugged to think/behave/feel better (psychopharmacology) is technically a cyborg. The range of these intimate human-machine relationships is mind-boggling. It's not just Robocop, it is our grandmother with a pacemaker ([[The Cyborg Handbook|Gray]], 322). - George P. Landow, Professor of English and Art History, Brown University. | |

| − | + | In "Cyborgology: Constructing the Knowledge of Cybernetic Organisms" -- the introduction to the ([[The Cyborg Handbook|Gray]], Introduction), four classes of cyborg are described: | |

| − | + | ||

| − | In "Cyborgology: Constructing the Knowledge of Cybernetic Organisms" -- the introduction to | + | |

| − | Cyborg technologies can be restorative, in that they restore lost functions and replace lost organs and limbs; | + | *Cyborg technologies can be restorative, in that they restore lost functions and replace lost organs and limbs; |

| + | *They can be normalizlng, in that thev restore some creature to indistinguishable normality; | ||

| + | *They can be ambiguously reconfiguring, creating posthuman creatures equal to but different from humans, like what one is now when interacting with other creatures in cyberspace or, in the future, the type of modifications proto-humans will undergo to live in space or under the sea having given up the comforts of terrestrial existence; | ||

| + | *They can be enhancing, the aim of most military and industrial research, and what those with cyborg envy or even cyborgphilia fantasize. | ||

| − | + | The latter category seeks to construct everything from factories controlled by a handful of "worker-pilots" and infantrymen in mind-controlled exoskeletons to the dream many computer scientists have-downloading their consciousness into immortal computers ([[The Cyborg Handbook|Gray]], 3). | |

| + | |||

| + | ===Related Topics === | ||

*[[Prosthesis]] | *[[Prosthesis]] | ||

*[[Google Buzz Discussion on Prosthesis]] | *[[Google Buzz Discussion on Prosthesis]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | __NOTOC__ | ||

Latest revision as of 07:15, 24 December 2010

Definition

Anything that is an external prosthetic device creates one into a cyborg. The idea of a cell phone being a technosocial object that enables an actor (user) to communicate with other actors (users) on a network (information exchange and connectivity) makes one into what David Hess calls low-tech cyborgs:

"I think about how almost everyone in urban societies could be seen as a low-tech cyborg, because they spend large parts of the day connected to machines such as cars, telephones, computers, and, of course, televisions. I ask the cyborg anthropologist if a system of a person watching a TV might constitute a cyborg. (When I watch TV, I feel like a homeostatic system functioning unconsciously.) I also think sometimes there is a fusion of identities between myself and the black box" (Gray, 373).

Types of Cyborgs

"According to the editors of The Cyborg Handbook, cyborg technologies take four different forms: restorative, normalizing, reconfiguring, and enhancing (Gray, 3). Cyborg translators are currently thought of almost exclusively as enhancing: improving existing translation processes by speeding them up, making them more reliable and cost-effective. And there is no reason why cyborg translation should be anything more than enhancing". Source: Cyborg Translation

Consumptive vs. Necessitative Prosthetics

I'd additionally define two additional types of cyborgs based on consumptive practices: those who attach prosthetics as a necessity, and those who attach them as an external representation of status and tribal affiliation. In the latter case, one's external prosthesis is chosen carefully and updated frequently. This is most often seen in middle classes, especially in the young offspring of these classes.

Other specialized cyborg types:

1. Cyborgs actually do exist; about 10% of the current U.S. population are estimated to be cyborgs in the technical sense, including people with electronic pacemakers, artificial joints, drug implant systems, implanted corneal lenses, and artificial skin. A much higher percentage participates in occupations that make them into metaphoric cyborgs, including the computer keyboarder joined in a cybernetic circuit with the screen, the neurosurgeon guided by fiber optic microscopy during an operation, and the teen gameplayer in the local videogame arcarde. "Terminal identity" Scott Bukatman has named this condition, calling it an "unmistakably doubled articulation" that signals the end of traditional concepts of identity even as it points toward the cybernetic loop that generates a new kind of subjectivity (Gray, 322).

2. This merging of the evolved and the developed, this integration of the constructor and the constructed, these systems of dying flesh and undead circuits, and of living and artificial cells. have been called many things: bionic systems, vital machines, cyborgs. They are a central figure of the late Twentieth Century. . . . But the story of cyborgs is not just a tale told around the glow of the televised fire. There are many actual cyborgs among us in society. Anyone with an artificial organ, limb or supplement (like a pacemaker), anyone reprogrammed to resist disease (immunized) or drugged to think/behave/feel better (psychopharmacology) is technically a cyborg. The range of these intimate human-machine relationships is mind-boggling. It's not just Robocop, it is our grandmother with a pacemaker (Gray, 322). - George P. Landow, Professor of English and Art History, Brown University.

In "Cyborgology: Constructing the Knowledge of Cybernetic Organisms" -- the introduction to the (Gray, Introduction), four classes of cyborg are described:

- Cyborg technologies can be restorative, in that they restore lost functions and replace lost organs and limbs;

- They can be normalizlng, in that thev restore some creature to indistinguishable normality;

- They can be ambiguously reconfiguring, creating posthuman creatures equal to but different from humans, like what one is now when interacting with other creatures in cyberspace or, in the future, the type of modifications proto-humans will undergo to live in space or under the sea having given up the comforts of terrestrial existence;

- They can be enhancing, the aim of most military and industrial research, and what those with cyborg envy or even cyborgphilia fantasize.

The latter category seeks to construct everything from factories controlled by a handful of "worker-pilots" and infantrymen in mind-controlled exoskeletons to the dream many computer scientists have-downloading their consciousness into immortal computers (Gray, 3).

Related Topics