File:Merton-anomie-typology-environmental-pressures.jpg

Merton’s theory of social structure and anomie

The other major contribution to the anomie tradition is Robert Merton’s theoretical analysis of "Social Structure and Anomie” (1938; 1957). Durkheim’s work provided the intellectual foundation for Merton’s attempt to develop a macro-level explanation of rates of norm-violating behavior in American society. But, in Merton’s hands, the anomie tradition advanced well beyond Durkheim’s singular concern with suicide to become a truly general sociological approach to deviance. In contrast to Durkheim, Merton bases his theory on sociological assumptions about human nature. Merton replaces Durkheim’s conception of insatiable passions and appetites with the assumption that human needs and desires are primarily the product of a social process: i.e., cultural socialization. For instance, people reared in a society where cultural values emphasize material goals will learn to strive for economic success.

Indeed, Merton focuses on the extreme emphasis on material goals that characterizes the cultural environment of American society. In this respect, Merton’s description of American society is quite similar to Durkheim’s observations regarding the unrelenting pursuit of economic gain in “the sphere of trade and industry.” However, Merton extends this materialistic portrait to include all of American society. Merton not only argues that all Americans, regardless of their position in society, are exposed to the dominant materialistic values, but that cultural beliefs sustain the myth that anyone can succeed in the pursuit of economic goals.

Anomie, for Durkheim, referred to the failure of society to regulate or constrain the ends or goals of human desire. Merton, on the other hand, is more concerned with social regulation of the means people use to obtain material goals. First, Merton perceives a “strain toward anomie” in the relative lack of cultural emphasis on institutional norms—the established rules of the game—that regulate the legitimate means for obtaining success in American society. Second, structural blockages that limit access to legitimate means for many members of American society also contribute to its anomic tendencies. Under such conditions, behavior tends to be governed solely by considerations of expediency or effectiveness in obtaining the goal rather than by a concern with whether or not the behavior conforms to institutional norms.

Together, the various elements in Merton’s theoretical model of American society add up to a social environment that generates strong pressures toward deviant behavior (1957: 146, emphasis in original):

[W]hen a system of cultural values extols, virtually above all else, certain common success-goals for the population at large while the social structure rigorously restricts or completely closes access to approved modes of reaching these goals for a considerable part of the same population,…deviant behavior ensues on a large scale.

This chronic discrepancy between cultural promises and structural realities not only undermines social support for institutional norms but also promotes violations of those norms. Blocked in their pursuit of economic success, many members of society are forced to adapt in deviant ways to this frustrating environmental condition.

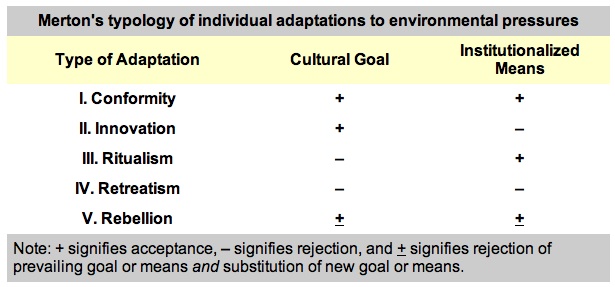

Just how do people adapt to these environmental pressures? Merton’s answer to this question is perhaps his single most important contribution to the anomie tradition. Merton presents an analytical typology, shown in the following table, of individual adaptations to the discrepancy between culture and social structure in American society.

These adaptations describe the kinds of social roles people adopt in response to cultural and structural pressures. Conformity, for instance, is a nondeviant adaptation where people continue to engage in legitimate occupational or educational roles despite environmental pressures toward deviant behavior. That is, the conformist accepts and strives for the cultural goal of material success (+) by following institutionalized means (+). Innovation, on the other hand, involves acceptance of the cultural goal (+) but rejection of legitimate, institutionalized means (-). Instead, the innovator moves into criminal or delinquent roles that employ illegitimate means to obtain economic success. Merton proposes that innovation is particularly characteristic of the lower class—the location in the class structure of American society where access to legitimate means is especially limited and the “strain toward anomie” is most severe. Driven by the dominant cultural emphasis on material goals, lower-class persons use illegitimate but expedient means to overcome these structural blockages. Thus, Merton’s analysis of innovation, like Durkheim’s analysis of anomic suicide, arrives at an environmental explanation of an important set of social facts; i.e., the high rates of lower-class crime and delinquency found in official records.

However, Merton goes on to explain a much broader range of deviant phenomena than just lower-class crime and delinquency. His third adaptation, ritualism, represents quite a different sort of departure from cultural standards than does innovation. The ritualist is an overconformist. Here, the pursuit of the dominant cultural goal of economic success is rejected or abandoned (-) and compulsive conformity to institutional norms (+) becomes an end in itself. Merton argues that this adaptation is most likely to occur within the lower middle class of American society where socialization practices emphasize strict discipline and rigid conformity to rules. This adaptation is exemplified by the role behavior of the bureaucratic clerk who, denying any aspirations for advancement, becomes preoccupied with the ritual of doing it “by the book.” Since the ritualist outwardly conforms to institutional norms, there is good reason to question, as does Merton, “whether this (adaptation) represents genuinely deviant behavior” (1957: 150).

Merton has no doubts about the deviant nature of his fourth adaptation, retreatism, the rejection of both cultural goals (-) and institutionalized means (-). Therefore, retreatism involves complete escape from the pressures and demands of organized society. Merton applies this adaptation to the deviant role “activities of psychotics, autists, pariahs, outcasts, vagrants, vagabonds, tramps, chronic drunkards, and drug addicts” (1957: 153). Despite the obvious importance of ritualism to the study of deviant behavior, Merton provides few dues as to where, in the class structure of society, this adaptation is most likely to occur. Instead, Merton’s analysis of retreatism has a more individualistic flavor than does his discussion of other types of adaptation. Retreatism is presented as an escape mechanism whereby the individual resolves internal conflict between moral constraints against the use of illegitimate means and repeated failure to attain success through legitimate means. Subsequently, Merton’s conception of retreatism as a private way of dropping out was given a more sociological interpretation by theorists in the subcultural tradition (Coward. 1959; Cloward & Ohlin, 1960).

The final adaptation in Merton’s typology, rebellion, is indicated by different notation than the other adaptations. The two ± signs show that the rebel not only rejects the goals and means of the established society but actively attempts to substitute new goals and means in their place. This adaptation refers, then, to the role behavior of political deviants, who attempt to modify greatly the existing structure of society. In later work (1966), Merton uses the term nonconformity to contrast rebellion to other forms of deviant behavior that are “aberrant.” The nonconforming rebel is not secretive as are other, aberrant deviants and is not merely engaging in behavior that violates the institutional norms of society. The rebel publicly acknowledges his or her intention to change those norms and the social structure that they support in the interests of building a better, more just society. Merton implies that rebellion is most characteristic of “members of a rising class” (1957: 157) who become inspired by political ideologies that “locate the source of large-scale frustrations in the social structure and portray an alternative structure which would not, presumably, give rise to frustration of the deserving” (1957: 156).

The appeal of Merton’s theory and a major reason for its far-reaching impact upon the field of deviance lies in his ability to derive explanations of a diverse assortment of deviant phenomena from a relatively simple analytical framework. This is precisely what a general theory of deviance must do. The utility or adequacy of Merton’s explanations of these forms of deviant behavior is a separate question, of course, a question that has led to a large body of additional theoretical and empirical work in the anomie tradition. Merton has continued to play an active part in the cumulative development of this macro-normative tradition through his published responses to various criticisms, modifications, and empirical tests of his theory of social structure and anomie (1957: 161—194; 1959; 1964; 1966; 1976).

Source: [1]

File history

Click on a date/time to view the file as it appeared at that time.

| Date/Time | Thumbnail | Dimensions | User | Comment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| current | 22:35, 20 November 2010 |  | 615 × 287 (62 KB) | Caseorganic (Talk | contribs) | Source: [http://deviance.socprobs.net/Unit_3/Theory/Anomie.htm] |

- You cannot overwrite this file.

File usage

There are no pages that link to this file.